I have always used some book or combination of books and paintings to create a closed system within which to compose a work of fiction. A particular setting, one century or another in one country or another, helps to accomplish this. Where it is impossible to create such a closed system, as in, say, writing about the present, or writing history rather than fiction, the use of a formal constraint can partially serve in its stead.

Cut-Ups

Cut-ups provide an instant closed system of lexical elements. One can shape the system by choosing to use one text alone or to merge several.

“In the beginning was my wishing… ”

In the example offered here, a collaboration at a distance with the writer Gretchen Henderson, I took one of the texts at her Galerie de Difformité and cut it up into segments of two, three or four words. Gretchen’s text (which can be downloaded here and in print from Lake Forest College Press) is itself built around quotations using the word you. Limited to her language and the language she had appropriated, I let the segments magnetize each other.

It was with the cut-up form that I first tested my idea that every literary work contains its own critique, like a statue hidden in a block of marble.

Constrained Writing

The primary value of constrained writing lies in the way it liberates the writer from her agenda, literary superego, and the ever-replaying internal tape loop. You cannot intend to say any particular thing when you write with constraints; you see what the constraint allows you to say. With many constraints you start by finding the words or phrases that obey the arbitrary rule, and then arrange them according to how they magnetize each other. The great delight is one of surprise and of discovering what you didn’t know you knew.

Constraints also offer a way to think about literary form that is not tied to and enforced by traditional merchandising categories, that escapes political ideologies set into ordinary language-uses. When you have familiarized yourself with some of the better-known constraints, you are ready to deploy them, or some variation of them, or simply what you have learned from them about language on another occasion. Lipograms (writing with a restricted set of letters) sensitize you to the emotive power of certain phonetic sounds by completely eliminating others; these musical properties, once learned, can then be deployed for dramatic effect in so-called “normal” writing. Filigranes (deploying all the connotations of a word left unspoken) make you see that every word implicitly contains numerous stories. “The Only the Wholly the” (barring signifying words such as nouns, verbs, and adjectives) shows how much thinking is done independent of identity and description; and so on.

Many people, when they first hear about this approach to writing, assume it is a kind of parlor game, fun perhaps but essentially trivial. The case for constraints’ value in the production of great fiction has been proved, but I believe they can also be used to open up new ways of investigating serious intellectual problems. For instance, I have an idea that every text contains its own critique. I first used this idea to compose “critical fictions,” a form where essay and narrative, or argument and poem blend. Later I applied this notion to the writing of history, particularly to investigations of those moments when the “normal” literature of the day and an historical event collide, forcing up new genres to deal with new experience. Whether these works of mine succeed is of course for the reader to decide, but they do show that constraint-based writing, considered by some to be apolitical and frivolous, may be quite otherwise.

As the composition of a novel must build on a firm understanding of sentence structure, the extension of constraint-based writing towards new long forms depends on some ease in the practice of its basic grammar.

The piece printed below was written using “The Prisoner’s Constraint.” The writer limits herself to letters without risers (such as h, b, k) and descenders (such as p, j, g). Imagine Houdini tied up in his strait jacket, curled inside a box.

ann a cosmos, sam a mess

ann is a universe

sam reveres ann

ann swims in waves, a venus in a scenic cove

sam roars in verse

ann is moon, sun, summer, music

i, a mere swain, mirror ann in rime

ann weaves roses, sews sam ear wear,

ann never muses on coins or norms,

ann seasons wearisome arizona,

ann rescues sam in zoos, museums,

mixes sam oreos in nacreous ooze,

ere ian, a con man, arrives in a van,

serves ann moose mousse, norse wine, orca nose in rain

some women swoon over mere caviar or cream

ann murmurs, move over, sam, moans, i am won

sam crosses rivers, meres, moors, ice masses, azure seas, some more moors

soars, an arrow in air, nears sami acres, veers, moves in

soon, as sam sami, a circus emcee, earns raves, seems sane

sam erases ann, curses ian, erases ian, woos zoe, snares ravens, amasses visions, answers voices, snares unicorns, sirens

as ann evanesces, sam measures rum in vain

now sam wears armor, rouses a seer

same seer reserves sam a mission, war on asia

or wisconsin

or maine

or rome,

or waco

sam murmurs mexico— i miss mexico…

enormous maize mazes, icons on canoes,

mines, worms, uranium, cousins in caves …

Download other Constrained Writing Texts

Translation

Abdelkrim Tabal and Distant Flames

I met the poet Abdelkrim Tabal through my friend Rabia Zbakh during the year I was living in Morocco. Tabal, one of Morocco’s best-known and best-loved poets, is unusual among his colleagues in that he writes in Arabic, not French. His work is closely tied to the winding streets of Chefchaouen, its mountain locale, Andalusian-style houses and revolutionary history. He composes his poems as he wanders the narrow streets; to walk is an essential part of his process.

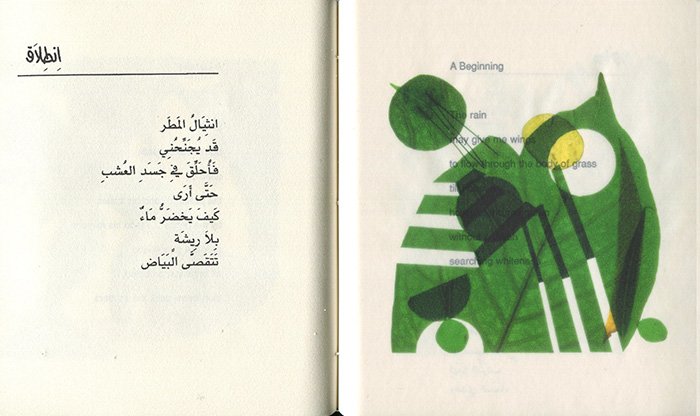

After I returned home, Rabia and I decided to collaborate on a translation of Distant Flames, one of Tabal’s more recent books. Another friend, the artist and printmaker Florence Neal, thought we should turn it into an artist’s book. The resulting bilingual text, some pages of which are shown below, was exhibited at the Center for Book Arts and Proteus Gowanus in NYC and at the Atelier Lacourière-Frélaut in Paris. The translations were also published in 26, Circumference and Marginalia.

With Tabal’s permission I have made available a pdf of the poems shown below with their translations.